|

Notes from Serra San Bruno, Italy |

This is the last of four emails that I sent to various friends when I found Internet access during my trip. You can read it, or skip to one of the other three:

You can also download the original ASCII email

archive, probably more suitable for printing.

My big bicycle trip ended around 5pm on Wednesday, September 15, after

exactly 80 days---of which 60 on the bike and the rest spent looking

around cities or nursing my Norwegian colds---and a total of 7029

kilometers (4369 miles). It's been tough to return to civilian life

after my little stint as a superhero. While those panniers were

strapped to my bike, I felt invincible, unstoppable. By the end, well

over a hundred miles of asphalt slipped beneath me every day.

6000-foot mountains were my appetizers.

The main course, every day, was a pound of pasta, three pounds of

full-fat yogurt or cottage cheese, half a pound of Nutella (for those

of you living beyond the outer limits of civilization, Nutella is a

delicious, heart-choking chocolate and hazelnut spread that most

people put on bread, but that I devour plain, with a spoon), a large

hunk of bread, some muesli, half a pound of honey, half a pound of

chocolate, half a pound to a pound of assorted sugar cookies, several

bananas and other fruit, and two gallons of water. Sometimes I'd

still be hungry, so I'd add a pound of mozzarella and a quarter pound

of ham, and maybe a little extra chocolate. All that, and I still

lost ten pounds over two months. I owned the road, I was king of the

mountains. I belched, spat, urinated, and blew my nose in full view

of oncoming traffic. I mooed at cows, bleated at sheep, and waved at

prostitutes. Grime collected under my fingernails. Dust covered my

hair and formed little brown gobs at the corners of my eyes. Sweat

drew pale trickles through the dust down my face. I blasted downhill

through remote mountain villages. I joined pacelines and outsprinted

guys on racing bikes. Ladies smiled with motherly tenderness, old men

reminisced about their youth, and adolescents burned with envy.

Occasionally an attractive girl even glanced at me, though most of

those were probably looks of disgust at the indelible sweat stains on

my jersey. Then, on the 15th, I cycled through the gate of my

father's lumber company to find him sitting on the office steps with a

camera ready. I was happy: happy to be home, happy to see my parents,

and happy to have accomplished something I had set out to do. But I

was also strangely empty: suddenly I was once again just "maxp",

professional nerd, and I really, really wanted to be a superhero

again.

The main course, every day, was a pound of pasta, three pounds of

full-fat yogurt or cottage cheese, half a pound of Nutella (for those

of you living beyond the outer limits of civilization, Nutella is a

delicious, heart-choking chocolate and hazelnut spread that most

people put on bread, but that I devour plain, with a spoon), a large

hunk of bread, some muesli, half a pound of honey, half a pound of

chocolate, half a pound to a pound of assorted sugar cookies, several

bananas and other fruit, and two gallons of water. Sometimes I'd

still be hungry, so I'd add a pound of mozzarella and a quarter pound

of ham, and maybe a little extra chocolate. All that, and I still

lost ten pounds over two months. I owned the road, I was king of the

mountains. I belched, spat, urinated, and blew my nose in full view

of oncoming traffic. I mooed at cows, bleated at sheep, and waved at

prostitutes. Grime collected under my fingernails. Dust covered my

hair and formed little brown gobs at the corners of my eyes. Sweat

drew pale trickles through the dust down my face. I blasted downhill

through remote mountain villages. I joined pacelines and outsprinted

guys on racing bikes. Ladies smiled with motherly tenderness, old men

reminisced about their youth, and adolescents burned with envy.

Occasionally an attractive girl even glanced at me, though most of

those were probably looks of disgust at the indelible sweat stains on

my jersey. Then, on the 15th, I cycled through the gate of my

father's lumber company to find him sitting on the office steps with a

camera ready. I was happy: happy to be home, happy to see my parents,

and happy to have accomplished something I had set out to do. But I

was also strangely empty: suddenly I was once again just "maxp",

professional nerd, and I really, really wanted to be a superhero

again.

I've procrastinated for a long time: weeks have passed since my last

mail from Ceske Budejovice. From there it was only a short ride to

tiny Krumlov, a fairy-tale town in Southern Bohemia that joins

Rothenburg ob der Tauber (Germany) and San Gimignano (Italy) on my

list of cities killed by their own prettiness, places in which nothing

real goes on any more because they've become what tourists expect them

to be. Don't let me discourage you from visiting Krumlov---it's very

picturesque---but don't let it be the only place you visit in Bohemia

unless you want to see only what you already imagine. There are many,

many more tourists than locals in Krumlov, and the locals are all

there to cater to the tourists. I encountered two main kinds of

tourists in Krumlov: wealthy German couples on a romantic weekend

getaway in their BMWs, and pennyless English-speaking backpackers who

got there on a Eurail ticket from Istanbul or wherever because that's

what the Lonely Planet book on Europe said was the best thing to do.

Some of the tourists like it so much that they stay a while, like the

Puerto Rican kid who runs one of the hostels for pennyless backpackers

and clearly burns with unrequited love for the pretty Czech girl who

runs one of the other hostels. There's torture even in paradise.

I've procrastinated for a long time: weeks have passed since my last

mail from Ceske Budejovice. From there it was only a short ride to

tiny Krumlov, a fairy-tale town in Southern Bohemia that joins

Rothenburg ob der Tauber (Germany) and San Gimignano (Italy) on my

list of cities killed by their own prettiness, places in which nothing

real goes on any more because they've become what tourists expect them

to be. Don't let me discourage you from visiting Krumlov---it's very

picturesque---but don't let it be the only place you visit in Bohemia

unless you want to see only what you already imagine. There are many,

many more tourists than locals in Krumlov, and the locals are all

there to cater to the tourists. I encountered two main kinds of

tourists in Krumlov: wealthy German couples on a romantic weekend

getaway in their BMWs, and pennyless English-speaking backpackers who

got there on a Eurail ticket from Istanbul or wherever because that's

what the Lonely Planet book on Europe said was the best thing to do.

Some of the tourists like it so much that they stay a while, like the

Puerto Rican kid who runs one of the hostels for pennyless backpackers

and clearly burns with unrequited love for the pretty Czech girl who

runs one of the other hostels. There's torture even in paradise.

Leaving the Czech Republic south of Krumlov you ride through a vast

and beautiful forest but eventually find yourself in a slightly dismal

little border town, the roadside lined with billboards that advertise

porn clubs and stands that sell grotesque plastic dwarves and giant

mushrooms to Austrian visitors looking for cheap garden ornaments.

You cross the border post, climb a little bit to the top of the ridge,

and suddenly northern Austria opens up before you in all its

incredible greenness. It's probably my imagination, but the grass

seems greener in Austria. The entire country looks landscaped, not a

blade of grass out of place. Fat cows lie in the sun contentedly

chewing the grass. Tidy roads snake across rolling meadows, joining

perfectly maintained wooden farmhouses and little villages where every

window-sill overflows with geraniums. Crews of men in orange outfits

canvass the roadside for discarded cigarette boxes and tiny scraps of

paper. Linz is a major industrial and commercial center, but it's

easy to cross, and soon you're back in splendid countryside that

continues uninterrupted all the way into Bavaria, the southeastern

"Land" of Germany. Of course, things aren't always as pretty as they

look: electoral billboards in Austria were obsessed with unemployment,

job security, and "family values," and the few comments I heard about

Turkish and Polish immigrants in Bavaria made me hope that less tidy

fields indicate a more liberal mindset. But I crossed the region too

quickly---just three days---to really get a feel for these issues: all

I can say for sure is that the cycling there is superb.

Leaving the Czech Republic south of Krumlov you ride through a vast

and beautiful forest but eventually find yourself in a slightly dismal

little border town, the roadside lined with billboards that advertise

porn clubs and stands that sell grotesque plastic dwarves and giant

mushrooms to Austrian visitors looking for cheap garden ornaments.

You cross the border post, climb a little bit to the top of the ridge,

and suddenly northern Austria opens up before you in all its

incredible greenness. It's probably my imagination, but the grass

seems greener in Austria. The entire country looks landscaped, not a

blade of grass out of place. Fat cows lie in the sun contentedly

chewing the grass. Tidy roads snake across rolling meadows, joining

perfectly maintained wooden farmhouses and little villages where every

window-sill overflows with geraniums. Crews of men in orange outfits

canvass the roadside for discarded cigarette boxes and tiny scraps of

paper. Linz is a major industrial and commercial center, but it's

easy to cross, and soon you're back in splendid countryside that

continues uninterrupted all the way into Bavaria, the southeastern

"Land" of Germany. Of course, things aren't always as pretty as they

look: electoral billboards in Austria were obsessed with unemployment,

job security, and "family values," and the few comments I heard about

Turkish and Polish immigrants in Bavaria made me hope that less tidy

fields indicate a more liberal mindset. But I crossed the region too

quickly---just three days---to really get a feel for these issues: all

I can say for sure is that the cycling there is superb.

And the cycling only got better. The first northeastern spurs of the Alps, the mountains of the Salzkammergut, gradually became visible just a few miles southwest of Linz. They rose like magic, twinkling in the sunlight, suspended in the sky above a layer of grayish-blue haze. As I rode up the river Inn from Rosenheim in Bavaria, the mountains grew ever taller around me; by Kufstein, where I reentered Austria, the Inn flows in a deep valley, 7000-foot peaks towering on either side. The Alps are marvelous for cycling: clean air, gorgeous views, challenging climbs, exhilarating descents. Weather and light change constantly and interact with the mountains and valleys, producing a dynamic spectacle of unique beauty.

Some days are grey and wet, like the morning on which I left Gries im

Sellrain, a village in the Austrian Alps, and headed into the clouds towards

the resort town of Kuehtai, 2017 meters (6656 feet) above sea level. Rainy

days are often the best for tackling big climbs: there is usually not much

wind, the chilly air helps delay fatigue, and rain drips off my helmet and

down my face, washing the salty sweat off my glasses and out of my eyes.

I've traveled the road to Kuehtai three times, and each time there have been

many cows, even by alpine standards. This time, cows even wandered into the

avalanche-protection tunnels that cover a good stretch of the upper part of

the road. The deep musical tinkle of cowbells was everywhere: loud and

resonating in the long concrete tunnels, fainter and prettier in the cloudy

whiteness that enveloped the pastures on either side of the road.

Some days are grey and wet, like the morning on which I left Gries im

Sellrain, a village in the Austrian Alps, and headed into the clouds towards

the resort town of Kuehtai, 2017 meters (6656 feet) above sea level. Rainy

days are often the best for tackling big climbs: there is usually not much

wind, the chilly air helps delay fatigue, and rain drips off my helmet and

down my face, washing the salty sweat off my glasses and out of my eyes.

I've traveled the road to Kuehtai three times, and each time there have been

many cows, even by alpine standards. This time, cows even wandered into the

avalanche-protection tunnels that cover a good stretch of the upper part of

the road. The deep musical tinkle of cowbells was everywhere: loud and

resonating in the long concrete tunnels, fainter and prettier in the cloudy

whiteness that enveloped the pastures on either side of the road.

Other times the weather is perfect, and I pant and squint under the

brilliant blue sky: sweat runs profusely down my face, collects in annoying

salty pools at the bottom of my glasses, drips off my nose and chin, and

glitters on my bicycle. But early in the morning or late in the afternoon

the weather is cooler and cycling is more pleasant, and the mountains glow

with magic light. One such Kodak moment was the top of Grosse Scheidegg, a

comparatively low pass (1962 meters, 6475 feet) in the Bernese Oberland

(Switzerland). My cousin Tommaso and I had huffed and puffed up the long

15% grade from Meiringen under a blistering mid-afternoon sun, but by the

time we reached the little resort of Rosenlaui, nestled under tall trees at

the edge of a vast green meadow, the air was cooler and the colors

brilliant. The rest of the climb was a struggle between Tommaso's sudden

burst of energy and my tendency to stop and take pictures every few meters.

But even Tommaso had to stop at the top of the pass to admire the sunset:

the vertical walls of the Wetterhorn (3701 meters, 12213 feet) glowed pink

to our left; behind us distant clouds and mountains stretching towards

Canton Unterwalden were lit by streaks of fire; and directly in front of us

the Schreckhorn (4078 meters, 13457 feet) and Eiger (3970 meters, 13101

feet) rose imposingly above the village of Grindelwald far below us in the

valley.

Other times the weather is perfect, and I pant and squint under the

brilliant blue sky: sweat runs profusely down my face, collects in annoying

salty pools at the bottom of my glasses, drips off my nose and chin, and

glitters on my bicycle. But early in the morning or late in the afternoon

the weather is cooler and cycling is more pleasant, and the mountains glow

with magic light. One such Kodak moment was the top of Grosse Scheidegg, a

comparatively low pass (1962 meters, 6475 feet) in the Bernese Oberland

(Switzerland). My cousin Tommaso and I had huffed and puffed up the long

15% grade from Meiringen under a blistering mid-afternoon sun, but by the

time we reached the little resort of Rosenlaui, nestled under tall trees at

the edge of a vast green meadow, the air was cooler and the colors

brilliant. The rest of the climb was a struggle between Tommaso's sudden

burst of energy and my tendency to stop and take pictures every few meters.

But even Tommaso had to stop at the top of the pass to admire the sunset:

the vertical walls of the Wetterhorn (3701 meters, 12213 feet) glowed pink

to our left; behind us distant clouds and mountains stretching towards

Canton Unterwalden were lit by streaks of fire; and directly in front of us

the Schreckhorn (4078 meters, 13457 feet) and Eiger (3970 meters, 13101

feet) rose imposingly above the village of Grindelwald far below us in the

valley.

Perhaps my best alpine ride this year, though, was that over Timmelsjoch,

which at 2509 meters (8280 feet) above sea level is the highest paved border

crossing between Austria and Italy. Today the border post no longer exists.

An Austrian and an Italian flag flap loudly in the wind, and the

inscription on a rectangular block of granite proclaims that peace and

border-less unity are the key to our prosperous future. Of course, in some

places peace and the future come more slowly than in others: down in the

Italian side of the pass, which became Italian at the Treaty of Versailles

that followed World War I, Italy is still viewed with some degree of

condescension and hostility. Over the years, I have often obtained better

service by speaking English or broken German rather than Italian. But

that's a whole other story. August 27 was a cold and foggy day on top of

Timmelsjoch. The climb from Oetztal, on the Austrian side, had been a game

of hide-and-seek with the clouds: first under heavy overcast, then up

through the clouds until I was sandwiched between two layers, puffy white

clouds below me and menacing grey ones above me, and finally still further

up, up into the menacing grey clouds themselves. But of course, every

German knows that Italy is the place to get a suntan, and indeed the descent

was glorious: 50 kilometers downhill all the way to Merano, resort town and

Italian apple-growing capital. Half a mile beyond the pass I was out of the

Perhaps my best alpine ride this year, though, was that over Timmelsjoch,

which at 2509 meters (8280 feet) above sea level is the highest paved border

crossing between Austria and Italy. Today the border post no longer exists.

An Austrian and an Italian flag flap loudly in the wind, and the

inscription on a rectangular block of granite proclaims that peace and

border-less unity are the key to our prosperous future. Of course, in some

places peace and the future come more slowly than in others: down in the

Italian side of the pass, which became Italian at the Treaty of Versailles

that followed World War I, Italy is still viewed with some degree of

condescension and hostility. Over the years, I have often obtained better

service by speaking English or broken German rather than Italian. But

that's a whole other story. August 27 was a cold and foggy day on top of

Timmelsjoch. The climb from Oetztal, on the Austrian side, had been a game

of hide-and-seek with the clouds: first under heavy overcast, then up

through the clouds until I was sandwiched between two layers, puffy white

clouds below me and menacing grey ones above me, and finally still further

up, up into the menacing grey clouds themselves. But of course, every

German knows that Italy is the place to get a suntan, and indeed the descent

was glorious: 50 kilometers downhill all the way to Merano, resort town and

Italian apple-growing capital. Half a mile beyond the pass I was out of the

clouds, on the edge of a rocky cliff 7000 feet above the bottom of Val

Passiria. The road is carved into the cliffside, switchbacks stacked almost

vertically one on top of the other; it descends gently at first and then

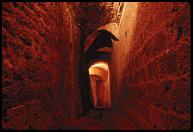

ever more steeply through a series of unlit tunnels. The last tunnel is the

longest, 500 meters of cold silent darkness disturbed only by the whir of my

freewheel and the dripping of water from the walls. The darkness, barely

punctured by the pinprick of light at the far end, was suddenly shattered by

a bright yellow light and the echoing roar of a motorcyclist entering the

tunnel behind me. But then I was out in the light again, wind in my ears

and the motorcycle reduced to a muffled rumble. To the right rose

Hoherfirst, "Monte Principe" in Italian (3403 meters, 11230 feet), one of

the eastern ramparts of the Oetztaler Alps, a wild area of tiny villages and

steep winding roads wedged between the craggy and vertical Dolomites to the

East and the imposing Ortler and Bernina massifs to the West. Clouds

enveloped the top of the mountain; the glacier appeared grey and brooding,

occasionally lit by streaks of sunlight that pierced the clouds. Below,

however, the valley was lush and welcoming, sprinkled with small wooden

farms. My ears popped as I plunged down into ever warmer and more fragrant

air: soon there were insects in the air, and the smell of grass and overripe

apples filled my nostrils. What a strange and beautiful ride: barely 30

kilometers separate an environment almost as harsh as that of North Cape

from some of the most fertile farmland in Italy!

clouds, on the edge of a rocky cliff 7000 feet above the bottom of Val

Passiria. The road is carved into the cliffside, switchbacks stacked almost

vertically one on top of the other; it descends gently at first and then

ever more steeply through a series of unlit tunnels. The last tunnel is the

longest, 500 meters of cold silent darkness disturbed only by the whir of my

freewheel and the dripping of water from the walls. The darkness, barely

punctured by the pinprick of light at the far end, was suddenly shattered by

a bright yellow light and the echoing roar of a motorcyclist entering the

tunnel behind me. But then I was out in the light again, wind in my ears

and the motorcycle reduced to a muffled rumble. To the right rose

Hoherfirst, "Monte Principe" in Italian (3403 meters, 11230 feet), one of

the eastern ramparts of the Oetztaler Alps, a wild area of tiny villages and

steep winding roads wedged between the craggy and vertical Dolomites to the

East and the imposing Ortler and Bernina massifs to the West. Clouds

enveloped the top of the mountain; the glacier appeared grey and brooding,

occasionally lit by streaks of sunlight that pierced the clouds. Below,

however, the valley was lush and welcoming, sprinkled with small wooden

farms. My ears popped as I plunged down into ever warmer and more fragrant

air: soon there were insects in the air, and the smell of grass and overripe

apples filled my nostrils. What a strange and beautiful ride: barely 30

kilometers separate an environment almost as harsh as that of North Cape

from some of the most fertile farmland in Italy!

In recent years, returning to Italy has felt just a little bit strange, as

if there were something out of place, like when you see a photo of yourself

and it looks familiar but a little odd, because it's the mirror image of the

face you see every day in the mirror. I told people that I'd ridden my bike

here from Norway, and it rarely crossed their minds that I might be Italian.

The first question was almost always the same: "Wow, great, where did you

learn to speak Italian so well?" Other times I was greeted with a "Deutsch?

Are you German?" And when I protested that I grew up here, in southern

Italy, I was dismissed without a thought: "What? No, you seem foreign."

Then there was the incredible bar tender in Capannoli, not far from the

picturesque town of San Gimignano, in Tuscany. I entered the cafe and asked

for a bottle of ice tea.

"You're American, aren't you?"

"Er, no, actually, I was born in Rome."

"Oh, Italian? Strange. But you live in America, don't you?"

"Er, yes."

"I'll tell you something else. I bet you live in the northern part of

America, Boston or New York, don't you?"

"What the ...? Yes, Boston. May I ask how you guessed?"

"It's easy, stamped on your forehead and across your back. Big bold

letters: USA. All of you, you're all the same."

I fumble with the change for the ice tea.

"And you know what? I bet you're an engineer, aren't you? Airplanes... or

computers, right? I know your type, you're all the same."

In recent years, returning to Italy has felt just a little bit strange, as

if there were something out of place, like when you see a photo of yourself

and it looks familiar but a little odd, because it's the mirror image of the

face you see every day in the mirror. I told people that I'd ridden my bike

here from Norway, and it rarely crossed their minds that I might be Italian.

The first question was almost always the same: "Wow, great, where did you

learn to speak Italian so well?" Other times I was greeted with a "Deutsch?

Are you German?" And when I protested that I grew up here, in southern

Italy, I was dismissed without a thought: "What? No, you seem foreign."

Then there was the incredible bar tender in Capannoli, not far from the

picturesque town of San Gimignano, in Tuscany. I entered the cafe and asked

for a bottle of ice tea.

"You're American, aren't you?"

"Er, no, actually, I was born in Rome."

"Oh, Italian? Strange. But you live in America, don't you?"

"Er, yes."

"I'll tell you something else. I bet you live in the northern part of

America, Boston or New York, don't you?"

"What the ...? Yes, Boston. May I ask how you guessed?"

"It's easy, stamped on your forehead and across your back. Big bold

letters: USA. All of you, you're all the same."

I fumble with the change for the ice tea.

"And you know what? I bet you're an engineer, aren't you? Airplanes... or

computers, right? I know your type, you're all the same."

So there you have it. Lean, sunburned, hair bleached by 4000 miles of sun and wind---yet I enter some random cafe in central Italy, and literally within 60 seconds the bar tender figures out I'm a computer geek from Boston. Wow! I didn't know MIT left visible scars across the forehead.

Whenever I return to Italy I am filled with wonder and frustration. I am

filled with wonder because I always forget the density of beauty in Italy.

With all due respect for Norway, I'd say there are tens of towns in Italy,

each one with the artistic and architectural wealth of all of Norway. There

is so much art that people become indifferent, unaware: you need to leave to

really appreciate it. All through middle and high school, I walked a mile

each way through downtown Rome to and from the school bus, almost blind to

sights on which today, as a "tourist," I would burn a whole roll of film

without a second thought. A few years ago some guy wrecked a statue

overlooking Bernini's "Fountain of the Four Rivers" because he thought it

would make a fine diving board. The basements of museums overflow with

busts, statues, columns, what have you: there is no place to display them

all, no one to restore and document them. Churches and palaces that would

make the centerpiece of many a Polish or Austrian town square are just one

more place in front of which to park a dumpster; grass grows among the

cobblestones, smog coats the once resplendent walls, and a stray dog

occasionally lifts a hind leg and adds to the rich, pungent odour of

decadence.

Whenever I return to Italy I am filled with wonder and frustration. I am

filled with wonder because I always forget the density of beauty in Italy.

With all due respect for Norway, I'd say there are tens of towns in Italy,

each one with the artistic and architectural wealth of all of Norway. There

is so much art that people become indifferent, unaware: you need to leave to

really appreciate it. All through middle and high school, I walked a mile

each way through downtown Rome to and from the school bus, almost blind to

sights on which today, as a "tourist," I would burn a whole roll of film

without a second thought. A few years ago some guy wrecked a statue

overlooking Bernini's "Fountain of the Four Rivers" because he thought it

would make a fine diving board. The basements of museums overflow with

busts, statues, columns, what have you: there is no place to display them

all, no one to restore and document them. Churches and palaces that would

make the centerpiece of many a Polish or Austrian town square are just one

more place in front of which to park a dumpster; grass grows among the

cobblestones, smog coats the once resplendent walls, and a stray dog

occasionally lifts a hind leg and adds to the rich, pungent odour of

decadence.

The same density of beauty applies to nature, too. During Christmas you can

sometimes ride out of my dad's lumber yard (800 meters, 2600 feet, above sea

level) under bright sunshine, climb up to 1400 meters (4600 feet) for some

snow-shoeing among the fir and beech trees, then plummet down through stands

of chestnuts, olive groves, and citrus plantations all the way to sea level,

and end the ride with a swim in water warmer than Massachusetts Bay in July:

all within 50 (relatively steep) kilometers (30 miles). Italy is small and

steep enough that it's easy to find such dramatic changes in environment.

On September 7, I left the splendid lake region near Lago Maggiore, just

minutes away from tall alpine peaks, and headed south. I crossed endless

farmland, huge rice paddies lined by rows of poplars, romantic at dawn under

their veil of mist lit by the rising sun. After a few hours hills appeared

around me; rice gave way to vines and olive trees as I climbed to Passo

Scoffera (674 meters, 2224 feet) through land that was once home to Fausto

Coppi, who is to Italian cycling as Babe Ruth is to American baseball. Then

a long descent fragrant with vineyards and pine trees, and I found myself in

Chiavari, on the Ligurian Riviera, where a brilliant sunset and dinner by

the ocean were the perfect finishing touches to a beautiful ride of 230

kilometers (142 miles).

The same density of beauty applies to nature, too. During Christmas you can

sometimes ride out of my dad's lumber yard (800 meters, 2600 feet, above sea

level) under bright sunshine, climb up to 1400 meters (4600 feet) for some

snow-shoeing among the fir and beech trees, then plummet down through stands

of chestnuts, olive groves, and citrus plantations all the way to sea level,

and end the ride with a swim in water warmer than Massachusetts Bay in July:

all within 50 (relatively steep) kilometers (30 miles). Italy is small and

steep enough that it's easy to find such dramatic changes in environment.

On September 7, I left the splendid lake region near Lago Maggiore, just

minutes away from tall alpine peaks, and headed south. I crossed endless

farmland, huge rice paddies lined by rows of poplars, romantic at dawn under

their veil of mist lit by the rising sun. After a few hours hills appeared

around me; rice gave way to vines and olive trees as I climbed to Passo

Scoffera (674 meters, 2224 feet) through land that was once home to Fausto

Coppi, who is to Italian cycling as Babe Ruth is to American baseball. Then

a long descent fragrant with vineyards and pine trees, and I found myself in

Chiavari, on the Ligurian Riviera, where a brilliant sunset and dinner by

the ocean were the perfect finishing touches to a beautiful ride of 230

kilometers (142 miles).

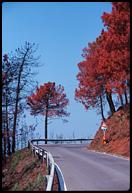

As you travel south, the environment becomes drier and the smells more

pungent. Plots of dry tilled earth cover rolling Tuscan countryside in a

pastel-colored checkered quilt, gentle shades of yellow, brown, ochre, and

red under an electric blue sky. Isolated farmhouses dot the hilltops. Long

rows of cypress trees demarcate the landscape and cast spectacular elongated

shadows. Further south, lone pines cling to rocky cliffs above turquoise

seas. Cicadas fill the air with their loud, rasping calls. Hornets and

wasps buzz in the dry grass. In the stifling heat, roadkill is shocking,

iridescent under swarms of bluebottles. Southern Italy appears in Goethe's

"Travels in Italy"; it inspired Mignon's song ("Kennst du das Land, wo die

Zitronen bluehn?") in "Wilhelm Meister"; it still calls to a few Germans or

Americans looking for something exotic. Occasionally you run into a herd of

sheep or cows blocking the road, an old herdsman and a couple mangy dogs

following behind. Along the coast, the air is rich with the smells of

citrus and of the sea; 900 meters (3000 feet) higher, the clinging, acrid

smoke of charcoal kilns adds to the rich scents of fir trees and wet earth.

As you travel south, the environment becomes drier and the smells more

pungent. Plots of dry tilled earth cover rolling Tuscan countryside in a

pastel-colored checkered quilt, gentle shades of yellow, brown, ochre, and

red under an electric blue sky. Isolated farmhouses dot the hilltops. Long

rows of cypress trees demarcate the landscape and cast spectacular elongated

shadows. Further south, lone pines cling to rocky cliffs above turquoise

seas. Cicadas fill the air with their loud, rasping calls. Hornets and

wasps buzz in the dry grass. In the stifling heat, roadkill is shocking,

iridescent under swarms of bluebottles. Southern Italy appears in Goethe's

"Travels in Italy"; it inspired Mignon's song ("Kennst du das Land, wo die

Zitronen bluehn?") in "Wilhelm Meister"; it still calls to a few Germans or

Americans looking for something exotic. Occasionally you run into a herd of

sheep or cows blocking the road, an old herdsman and a couple mangy dogs

following behind. Along the coast, the air is rich with the smells of

citrus and of the sea; 900 meters (3000 feet) higher, the clinging, acrid

smoke of charcoal kilns adds to the rich scents of fir trees and wet earth.

All this beauty, yet often I feel angry and frustrated by how much better

Italy could be. Postal clerks always perform personal favors by accepting

my mail. I went to the "carabinieri," the military police, for routine

passport bureaucracy, and they didn't even have a copier with which to xerox

my passport: I had to cycle to my dad's company to find a working

photocopier. Waiters in Pisa smirked at "dumb" tourists, cockily certain

that the leaning tower and other wonderful attractions will continue to

bring in the hordes, no matter how bad the service. Construction on a road

near my home town began when I was in elementary school. I was a graduate

student by the time a couple of miles were finally finished, over a decade

past schedule and having consumed the budget for the entire 20- or 30-mile

planned stretch. Hospitals, especially in the south, are usually filthy and

always scary. To quote my father, who's lived there for half a century,

"the best hospital in the south is the airport." As long as the air traffic

controllers aren't on strike, of course. Huge steel mills and other

mastodontic industrial works deface otherwise beautiful southern coastline,

unused and rusting monuments to misguided state-financed industrialization

projects that took into account the wallets of local politicians rather than

the economic viability of such ventures. Italo Calvino wrote a wonderful,

bitter novel entitled "La Speculazione Edilizia" (roughly translated,

"Speculation on Housing Construction"), set on the Ligurian Riviera that I

mentioned earlier. It describes a problem that unfortunately is not limited

to the Ligurian coast: ugly housing blocks and cheap summer homes sold at

exorbitant prices clutter and disfigure scenic places from Genova to Amalfi,

from Palermo to Brindisi. Often, houses are built on dangerous or

unsuitable terrain, and no one cares until an earthquake or landslide kills

a few people: then there's a lot of wailing and hand-wringing, mamma mia!,

but after a few days everything's back to normal, and the homeless settle

into prefab containers where they'll live for the next twenty years while

their destroyed homes are ever so speedily rebuilt. Urban planning, so

highly developed as far back as the Romans, has somehow been forgotten.

Many cities are ancient jewels surrounded by miles of anonymous and

dispiriting housing blocks worthy of the worst Stalinist tradition. Poor

traffic planning and a mad passion for cars result in gargantuan traffic

jams, hellish smog pits punctuated by the high-pitched buzz of motor

scooters and the colorful oaths and hand gestures of cab drivers.

All this beauty, yet often I feel angry and frustrated by how much better

Italy could be. Postal clerks always perform personal favors by accepting

my mail. I went to the "carabinieri," the military police, for routine

passport bureaucracy, and they didn't even have a copier with which to xerox

my passport: I had to cycle to my dad's company to find a working

photocopier. Waiters in Pisa smirked at "dumb" tourists, cockily certain

that the leaning tower and other wonderful attractions will continue to

bring in the hordes, no matter how bad the service. Construction on a road

near my home town began when I was in elementary school. I was a graduate

student by the time a couple of miles were finally finished, over a decade

past schedule and having consumed the budget for the entire 20- or 30-mile

planned stretch. Hospitals, especially in the south, are usually filthy and

always scary. To quote my father, who's lived there for half a century,

"the best hospital in the south is the airport." As long as the air traffic

controllers aren't on strike, of course. Huge steel mills and other

mastodontic industrial works deface otherwise beautiful southern coastline,

unused and rusting monuments to misguided state-financed industrialization

projects that took into account the wallets of local politicians rather than

the economic viability of such ventures. Italo Calvino wrote a wonderful,

bitter novel entitled "La Speculazione Edilizia" (roughly translated,

"Speculation on Housing Construction"), set on the Ligurian Riviera that I

mentioned earlier. It describes a problem that unfortunately is not limited

to the Ligurian coast: ugly housing blocks and cheap summer homes sold at

exorbitant prices clutter and disfigure scenic places from Genova to Amalfi,

from Palermo to Brindisi. Often, houses are built on dangerous or

unsuitable terrain, and no one cares until an earthquake or landslide kills

a few people: then there's a lot of wailing and hand-wringing, mamma mia!,

but after a few days everything's back to normal, and the homeless settle

into prefab containers where they'll live for the next twenty years while

their destroyed homes are ever so speedily rebuilt. Urban planning, so

highly developed as far back as the Romans, has somehow been forgotten.

Many cities are ancient jewels surrounded by miles of anonymous and

dispiriting housing blocks worthy of the worst Stalinist tradition. Poor

traffic planning and a mad passion for cars result in gargantuan traffic

jams, hellish smog pits punctuated by the high-pitched buzz of motor

scooters and the colorful oaths and hand gestures of cab drivers.

I should stop: when I start on one of these rants, I just go on and on. Leo

Longanesi, famous Italian graphic artist and man of letters, was of course

much more elegant and succinct in his criticism: "Gli italiani preferiscono

le inaugurazioni alla manutenzione" ("Italians prefer inaugurations to

maintenance"). As a cyclist, you understand this truth viscerally, all the

way to the core of your jarred joints, as you roll off Swiss asphalt and

onto Italian asphalt. Much further south, road signs serve as target

practice for local gangsters, hunters, and other trigger-happy Latin males.

Those parts that are not blown away by bullets are made illegible by streaks

of rust that flow down from the bullet holes when it rains. "Raccolta

differenziata," "separate collection" for different kinds of garbage, such

as glass and paper, has recently been introduced with great media fanfare in

southern Italy. Colorful green and yellow containers decorate the odd

street here and there, but mostly they serve as homes for stray cats and

dogs. In many places, people haven't yet figured out the use of normal

trash cans and dumpsters. Garbage bags and old washing machines lie in tall

grass by the roadside, beautiful sights and delicious smells for the unwary

bicycle tourist. Maybe as I grow older I'll learn to just enjoy the good

and make the best of the less good; patience is supposed to be an Italian

trait.

I should stop: when I start on one of these rants, I just go on and on. Leo

Longanesi, famous Italian graphic artist and man of letters, was of course

much more elegant and succinct in his criticism: "Gli italiani preferiscono

le inaugurazioni alla manutenzione" ("Italians prefer inaugurations to

maintenance"). As a cyclist, you understand this truth viscerally, all the

way to the core of your jarred joints, as you roll off Swiss asphalt and

onto Italian asphalt. Much further south, road signs serve as target

practice for local gangsters, hunters, and other trigger-happy Latin males.

Those parts that are not blown away by bullets are made illegible by streaks

of rust that flow down from the bullet holes when it rains. "Raccolta

differenziata," "separate collection" for different kinds of garbage, such

as glass and paper, has recently been introduced with great media fanfare in

southern Italy. Colorful green and yellow containers decorate the odd

street here and there, but mostly they serve as homes for stray cats and

dogs. In many places, people haven't yet figured out the use of normal

trash cans and dumpsters. Garbage bags and old washing machines lie in tall

grass by the roadside, beautiful sights and delicious smells for the unwary

bicycle tourist. Maybe as I grow older I'll learn to just enjoy the good

and make the best of the less good; patience is supposed to be an Italian

trait.

Enough pseudo-sociological randomness, and on to more practical stuff. For the bike nerds among you, and for those thinking of going on an extended bike trip, I thought I'd share a few details about equipment and technical problems.

I hope that you've enjoyed my sporadic email notes, or at least that

they weren't totally annoying. In a couple of weeks I'll be back in

the US, where 2000 slides wait to be sorted. I hope to find a few

good ones: when, or if, I finish my planned web photo-diary, I'll send

one last mail to this list to announce the URL. If you ever need a

bike touring partner, you know whom to call.

| Top |